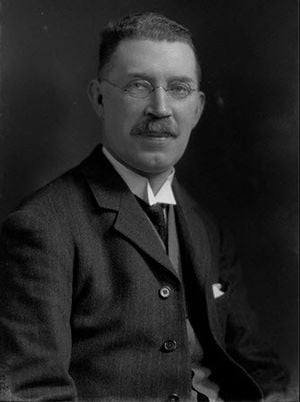

Arberry is a public intellectual, well known in the Anglo-American world. Born into a poor and puritanical Christian family, A. J. Arberry (1905-69) lost his faith largely as a result of reading George Bernard Shaw. Transformed by his encounter with Islamic mysticism, however, Arberry resumed actively practicing Christianity, with the realization, no doubt learned from Rumi, that “Jew, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Parsi — all sorts and conditions of men” were and are illuminated by God, “the One Universal,” whose light, as the Koran states, is neither of East nor West (MPR 2: xiii-xiv).

Arberry met and began studying with Nicholson at Cambridge in 1927, after completing the examinations in classics; reflecting over his career toward the end of his life, Arberry described his encounter with Nicholson as the turning point of his life. He went on to obtain his doctorate in 1936 and after stints teaching classics in Cairo, as a librarian in the India Office and as Professor of Persian at the University of London, he returned to Cambridge to assume the Sir Thomas Adams Chair of Arabic after the death of Nicholson, a position he held until his death in 1969.

Translator of the Koran and many works from Persian and Arabic, as well as an editor of manuscripts, the prolific Arberry also authored general introductions to Sufism and Middle Eastern literature, as well as two histories of British orientalists. Extensive as had been his teacher, Nicholson’s, work on Rumi, Arberry did manage to find some solid ground of his own to cover, contributing to our understanding of Rumi over the course of his career with a number of scholarly translations. First, taking a cue from the popularity of FitzGerald’s translation of Khayyam, Arberry culled a selection from the quatrains found in the Divan-e Shams (though not all of these can be considered genuine compositions of Rumi), and put them into English verse as The Ruba‘iyat of Jalal ul-Din Rumi (London: Emery Walker, 1949). He next translated the important collection of Rumi’s lectures, Fihe ma fih, as Discourses of Rumi (London: John Murray, 1961; several reprints).

Arberry was hoping, toward the end of his life, to publish a complete study of the life, writings and teachings of Rumi, including “an extended analysis of the contents, pattern and doctrine of the Masnavi”. He did not live to complete this task, but he did make several further contributions to the spread of knowledge about Rumi, all of which remain quite important.

As a work for the general public, Arberry prepared two hundred of the stories told by Rumi as Tales from the Masnavi and More Tales from the Masnavi (London: Allen & Unwin, 1961 and 1963, respectively), the first of which includes an introductory sketch about the background and nature of Rumi’s magnum opus. Arberry described his method as “putting the original verse – couplets into rhythmical prose,” to which spare notes were added.

After presenting the two hundred most interesting tales, Arberry hoped to present translations from “the didactic passages which intersperse, and very frequently interrupt these tales.” A methodical arrangement of such passages would make Rumi’s “theological and mystical doctrine self-explanatory” and the role that the tales play in “illustrating that somewhat complex and abstruse doctrine” would become clear. Arberry did not, however, manage to bring this plan to completion; instead, he next presented an extended selection of Baha al-Din Valad’s discourses, which he included in a book of source texts called Aspects of Islamic Civilization as Depicted in the Original Texts (New York: A.S. Barnes; London: Allen & Unwin, 1964; several reprints).

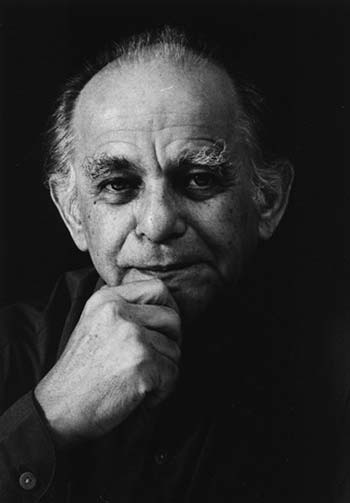

In 1963, Ehsan Yarshater, Professor of Persian at Columbia University and editor of the Persian Heritage series (and now editor of the remarkable Encyclopaedia Iranica) invited Arberry to make further selections of the Divan-e Shams available to English readers. The two resulting volumes, Mystical Poems of Rami (London: Allen & Unwin; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968; reprint 1972) and Mystical Poems of Rami, 2 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979; reprint, 1991), provided literal lineated prose versions of four hundred ghazals, as Arberry’s most important contribution to the dissemination of the poetry and thought of Rumi in the West. Though he did not live to see the publication of the second volume, the manuscript of which was annotated and prepared for publication by Professor Hasan Javadi.

Arberry passed away in 1969. He has exercised an enduring influence on the current generation of translators; both those who know and those who do not know Persian rely, at least in part, upon his literal renderings of the poems from the Divan-e Shams for the meaning of what Rumi wrote.

Reference: Lewis, Franklin D. Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi. Oxford: One World Publications (UK), 2000, p. 533-537.