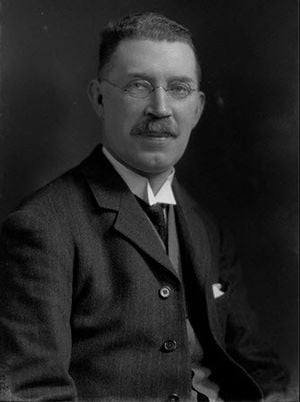

R. A. Nicholson (1868-1945) in all his years of the study of Persian and Arabic never once visited the Middle East and never learned to speak the languages, whose literatures were the object of his study, though he could read and interpret them better than most native speakers. After losing interest in his first field, classics, Nicholson turned to Arabic and Persian and became a lecturer in Persian, a position he held from 1902 until the death of E.G. Browne in 1926, at which point Nicholson became Sir Thomas Adams Professor of Arabic (1926-33).

Nicholson’s first and greatest love was Jalal al-Din Rumi. At the age of thirty, Nicholson published his Selected Poems from the Divan-e Shams Tabriz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1898), which provided the first text- critical edition of a collection of poems by Rumi, along with facing English translation, introduction and extensive notes.

Although Nicholson’s verse translations from Persian and Arabic have not aged particularly well, many in Edwardian England, including his teacher Browne, considered them quite beautiful. Nicholson’s prose translations, however, are not so dated as his verse, and in a 1924 article in the Centenary Supplement to the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Nicholson first introduced the West to the Discourses of Rumi, “Fihe ma fih”. He later published brief specimens of the work in translation, suggesting to his student, A. J. Arberry, the idea of providing a full translation. Nicholson’s greatest work, though, was his edition, translation and commentary on Rumi’s “Masnavi”.

Not contented simply to work from the available printed editions of the Masnavi and the existing Turkish commentaries, Nicholson set about editing the more than 25,000 lines of the poem from a variety of medieval and early modern manuscripts. The task consumed eight volumes and fifteen years, from 1925 to 1940, and it also sapped the power of sight from Nicholson’s eyes. But the result was an excellent critical edition of the Persian text, and a full translation, supplemented by extensive notes and commentary intended to facilitate the scholarly study of the text, particularly the theosophy of Rumi. The notes include references to earlier Sufi doctrines and poets, giving specific relevant background information to help with the understanding of Rumi’s allusions.

Before this scholarly project was completed, Nicholson condensed the results of his labors on the Masnavi into a collection of under two hundred pages intended for a popular audience. “The Tales of Mystic Meaning, Selections from the Mathnawi of Jalal-ud-Din Rumi” (London: Chapman & Hall; New York: Frederick Stokes, 1931) presented fifty-one of the choicest stories with an introduction in which Nicholson explained something of the ramifications of the Masnavi and the nature of Rumi’s teachings.

Nicholson had intended to produce an authoritative account of Rumi’s life, but did not live to fulfill this expectation. He did compile a selection of poems illustrating Sufi doctrine and experience as depicted by the greatest of Iranian mystical poets, Jalalu’I-Din Rami, which appeared posthumously, edited by Nicholson’s erstwhile student, A. J. Arberry, as “Rumi: Poet and Mystic” (London: Allen & Unwin, 1950).

Nicholson’s dedication of his life’s work to Rumi sparked the interest of many other scholars and amateurs, and his Persian edition of the text of the Masnavi remains the most widely read and referenced text of the poem not only in the West, but also in India and in Iran itself. When Nicholson died, Badi‘ al-Zaman Foruzanfar, who perhaps later surpassed Nicholson as this century’s most prolific Rumi scholar, composed a long elegy in Persian verse to pay him homage.

Reference: Lewis, Franklin D. Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi. Oxford: One World Publications (UK), 2000, p. 531-533.