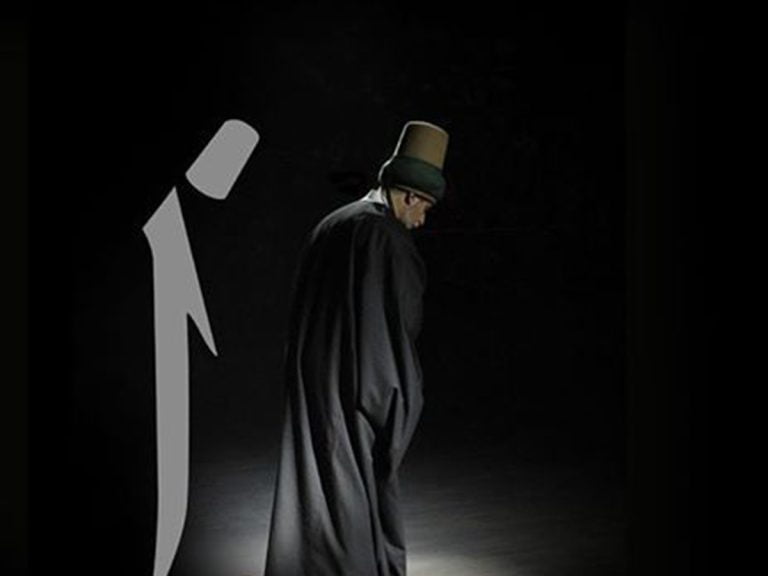

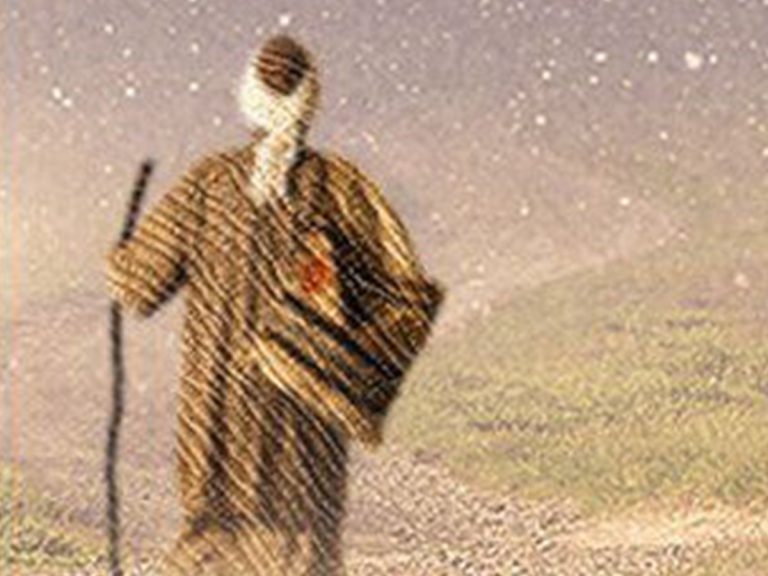

Rumi’s life seemed to have been a fairly normal one for a religious scholar: teaching, meditating, helping the poor, until in the late fall of 1244 when he met a stranger, who put a question to him. Shams means “sun” in Arabic. The full title of the dervish who wholly transferred Rumi’s life and thoughts, Shams al-Din Tabrizi, means “The Sun of Faith from Tabriz”. Aflaki (614) gives his full name as Shams al-Din Mohammad b. ‘Ali b. Malek-e Dad, but grandiloquent titles and honorific addresses were obligatory in polite society in the medieval period, and Shams is accorded his share. Sepahsalar (Sep 122) gives him the following caravan of honorific titles: King of the Saints (Soltan al-owlia?) and those who have attained unto God (al-vaselin), the Spiritual Axis of the Gnostics (Qoth al-‘arefin), God’s Proof for the Faithful and the Heir (Vares) of the Prophets and Messengers. Rumi evokes Shams by many other less cliched and therefore more impressive titles, among them Sea of Mercy (Bahr-e rahmat), Sun of Grace (Khworshid-e lotf), the Mighty Monarch (Khosrov-e a‘zam), the Lord of the Lords of Mysteries (Khodavand-e khodavandan-e asrar), The King of Kings of the Spirit (Soltdn-e soltanan-e jan) and Pure Light (Nur-e motlaq).

Though we cannot be entirely certain of the nature of their first meeting, we can take Shams’ account into consideration. Whilst most of the Magalat is in Persian, Shams describes his first meeting with Rumi and the words they exchanged in Arabic (Maq 685): “The first thing I spoke about with him was this: How is it that Abayazid did not need to follow [the example of the Prophet], and did not say “Glory be to Thee” or “We worship Thee?

Rumi hearing the depth out of which the question came, fell to the ground. He was finally able to answer that Mohammad was greater, because Bastami had taken one gulp of the divine and stopped there, whereas for Mohammad the way was always unfolding. There are various versions of this encounter but whatever the facts, Shams and Rumi became inseparable.

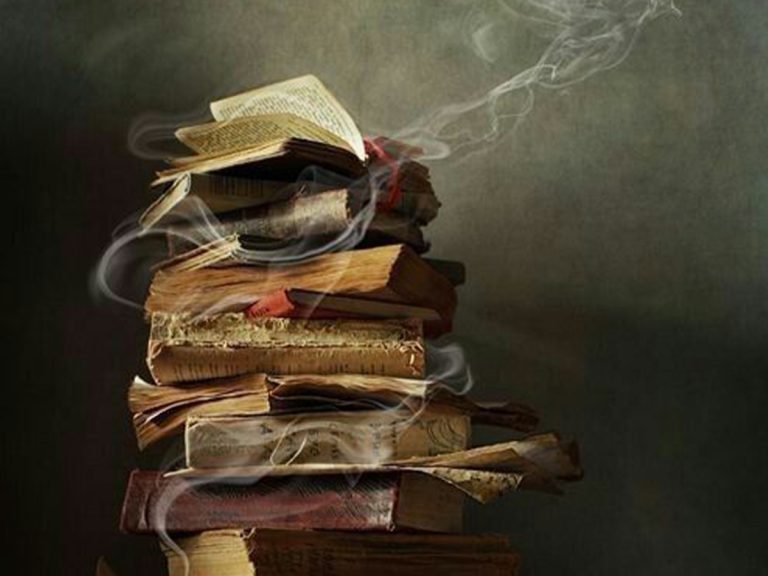

Rumi was immediately drawn to this mysterious figure, who turned out to be a wandering mystic. The two began to spend endless hours together in retreat. What was shared by the pair during this time remains a mystery that can only be guessed from the volumes of poetry that it inspired. Even in Masnavi, where Rumi makes painstaking efforts to communicate his teachings as clearly as possible for the benefit of his students, he nonetheless expresses his willingness to disclose anything about his experiences with Shams. Rumi explains that those experiences were beyond the capacity of others to understand:

Please don’t request what you can’t tolerate

A blade of straw can’t hold a mountain’s weight

It is clear that Rumi recognized Shams as a profound mystic, the like of whom he had never encountered before and that for him, Shams was the most complete manifestation of God. Rumi innovatively named his own collection of lyrical poems as ‘the collection of Shams’ (in Persian: Divan-e Shams) rather than as his own collection and also included Shams’ name in place of his own at the end of many of his ghazals, where by convention the poet would identify himself. This can be seen as acknowledgement of the all-important inspiration that Shams had provided for him to write such poetry.

References

Arberry, A. J.Discourses of Rumi: A translation of Fihi Ma Fihi, Samuel Weiser, New York, 1972.

Lewis, Franklin D. Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi. Oxford: One World Publications (UK), 2000.

Rumi, The Masnavi: Book One, translated by Jawid Mojaddedi, Oxford World’s Classics Series, Oxford University Press, 2004.

Lewisohn L. The Philosophy of Ecstasy: Rumi and the Sufi Tradition, Nicosia, London, Rumi Institute and I.B. Tauris, 2011.