Like Sana’i and the other Sufis before him, Rumi held that the true meaning or significance (ma‘ni) of things and words and religious praxis must be discovered and revealed beyond the outward surface or zaher. In philosophical and mystical discourse, particularly in a Shiite context, zaher is often contrasted with baten in the respective senses of exoteric and esoteric, but ma‘ni does not so strongly suggest allegorical and abstruse symbolic interpretation as does the word baten, rather, ma‘ni suggests the real experiential comprehension achieved through self- discipline and purity, not through easy or superficial or worldly understanding. Rumi continually urges his readers to discard the husk and taste the inner fruit of religion:

‘What is skin but multi-colored words

reflections upon a colorless pool Words are like rinds and meanings the kernels

Words are like forms and meanings their spirits

The skin a faulty meaning can conceal

or jealously guard good meaning from view

(M1:1096-8)

The conflicts among men stem from names

Trace back the meaning and achieve accord

(M2:3680)

Though Muslims were encouraged to read the Koran in the medieval period, widespread illiteracy, as well as ignorance of Arabic among the Turkish- and Persian-speaking laity, often made this impractical or impossible for most people. This fact, combined with the general tendency to orthopraxy in Middle Eastern societies, meant that imitation of authorities played a large part in matters of ritual, worship and so forth. Islamic law calls for imitation of the legal decrees of those legal scholars recognized among the wisest of the age. Indeed, Rumi believes in the need for a spiritual guide, and advises that one should not cut oneself off from one’s spiritual community until the truth has been realized within one, like a pearl formed in its shell. But if one imitates a guide out of selfish desire, it will deprive one of illumination (M2:568-9).

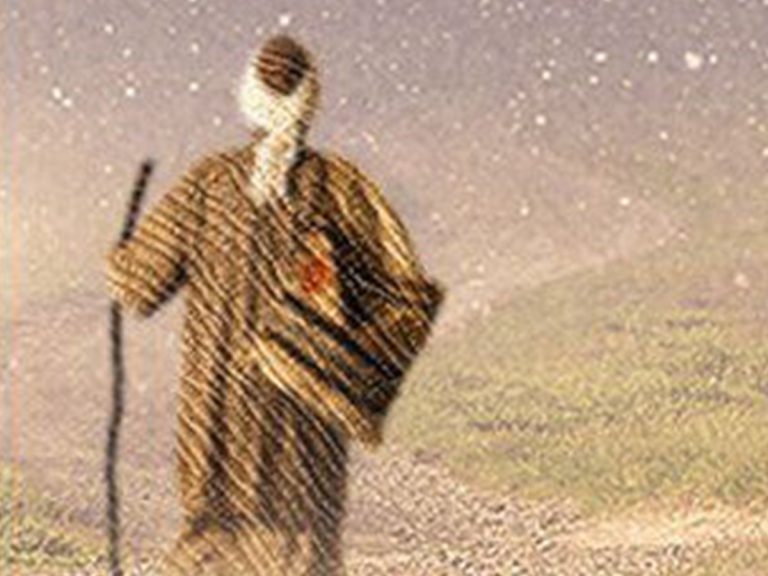

Although one must follow the true spiritual guide, a spiritual orientation sometimes entails a rejection of dogmatic imitation (taglid) and conformity, which can hamstring our intellect and mislead us. Rumi tells the story of a Sufi traveler invited to dine and dance with a group of impoverished and caddish dervishes, who decide to sell his donkey while distracting him. They begin to dance and the Sufi, carried away by emotion, joins with them as they sing over and over again, “the donkey’s gone.” The Sufi’s servant comes to inform him of the theft of his donkey, but concludes from the song that his master knew and did not care.

Rumi explains in Discourse 36 that just as God is the root of all being and creation secondary branches, so too love is at the root of the outward aspect of the things we see in this world. Love gives rise to a multiplicity of forms, but these are secondary and non-essential (Fih 139). This allows Rumi to adopt a very constructive ecumenical attitude toward various creeds. It is tempting to compare the Muslim poet Rumi’s attitude to that of the Christian poet Dante; as Nicholson observed in 1914, Dante “falls far below the level of charity and tolerance” advocated and practiced by Rumi.’

References

Lewis, Franklin D. Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi. Oxford: One World Publications (UK), 2000.