The Sufi practice that is discussed the most in the early manuals of Sufism is listening to music, commonly referred to as ‘musical audition’ (Sama’). Sama‘ ideally involves the use of poems and music to focus the listener’s concentration on God and perhaps even induce a trance-like state of contemplative ecstasy (vajd, hal). When this happens, it often moves the listener to shake his arms or dance. It is therefore a kind of motile meditation or deliberative dancing, a mode of worship and contemplation. This was one of Rumi’s favorite activities, and consequently became the most distinctive practice of the order of Sufis which his disciples later formed, the Mevlevis or ‘Whirling Dervishes’.

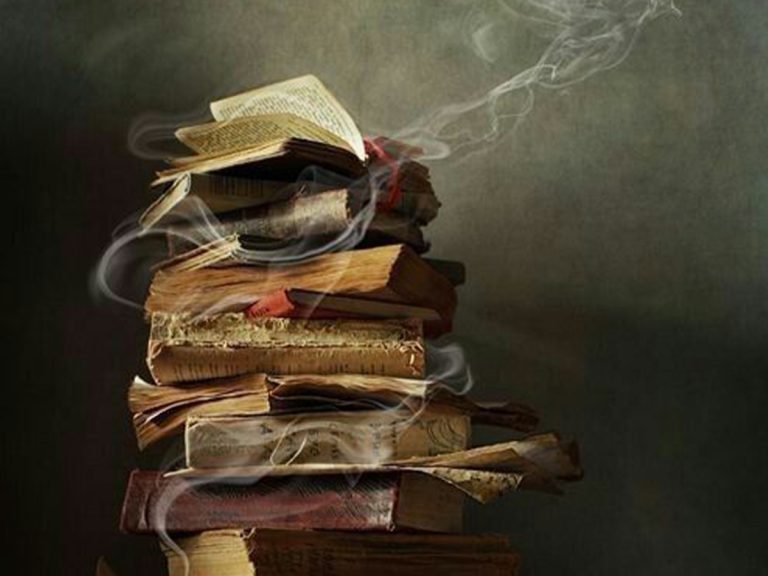

The manuals of Sufism had thoroughly covered the subject of sama‘ by the time of Rumi, giving it a theoretical justification. In the mid-eleventh century, Hojviri devotes the last chapter of his “Kashf al-mahjub” to it, first proving that the Prophet had encouraged the chanting of the Koran, and then proving that the Prophet had also listened to poetry. Hojviri goes on to show that the Prophet did allow singing and the playing of melodies. Of course, music can provoke a person’s base passions or it can send him into transports of spiritual bliss. The act of listening to music was not, therefore, in itself wrong or evil, but it could become sinful if the listener responded improperly. Dancing was not approved by Hojviri, though he did not forbid it, explaining that the movements of the dervishes in sama‘ are not dancing but responding to mystical ecstasy. The theologians, however, were divided about whether or not poems should even be recited in the mosque.

Enter into sama‘, for you will find increase of that which you seek in it. Sama‘ was forbidden to the people because they are preoccupied with base passions. When they perform sama‘ their reprehensible and hateful characteristics increase and they are moved by pride and pleasure. Of course sama‘ is forbidden to such people. On the other hand, those people who quest for and love truth, their characteristics intensify in sama‘ and none but God enter their field of vision at such times. So, sama‘ is permissible to such people.

Rumi obeyed this instruction and attended sama‘ and observed with his own eyes in the state of sama‘ that which Shams had indicated, and he continued to practice and follow this custom until the end of his life. Indeed, Rumi became quite enamored with the ritual of turning and singing verse. Sama‘ became Rumi’s food of divine love, and he played it on and on.

References

Lewis, Franklin D. Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi. Oxford: One World Publications (UK), 2000.

Arberry, A. J. Discourses of Rumi, A translation of Fihi Ma Fihi, Samuel Weiser, New York, 1972.