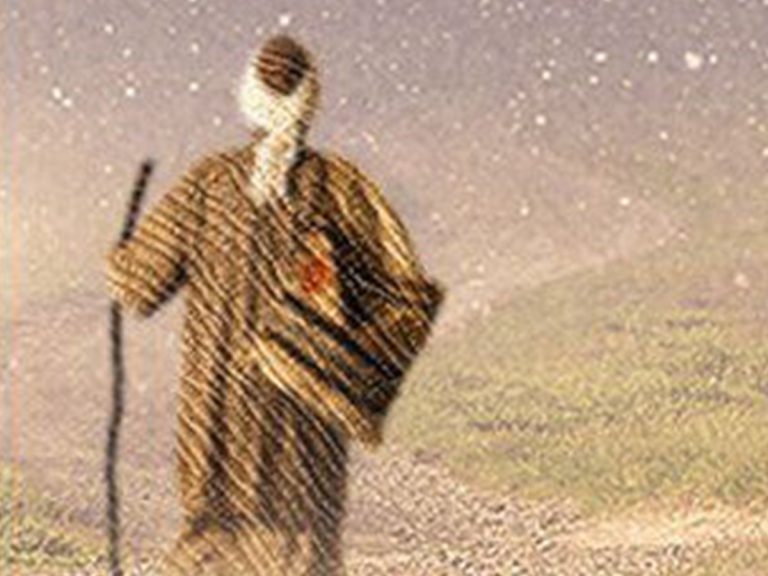

For Rumi, the creation is a multichrome and multiform manifestation of the single resplendent whiteness that is God. The creation is the explosion of this primal colorlessness into form and aspect, thereby producing the illusion of individuation, separation, distinction and opposition. Rumi explains that everyone views existence through a glass of a particular color, seeing truth refracted in a different hue, depending on his vantage point. One looks through a blue glass and sees blue, another through a red glass and sees red. Only the prophet, the true Imam, or exemplar, can look above the prism and discern the real and unrefracted whiteness of the light. Elsewhere he speaks of the unichromity of Jesus, whose purity could merge a myriad-colored coat into simple unrefracted light. Mortal existence is lived out, however, below this plane, in the refracted rays of this light, and this gives rise to bewildering mysteries. How did color appear from colorlessness, and to what aim? Do apparent opposites really contend, or is it all illusion?

Using the Persian royal game of polo as a metaphor, Rumi postulates that the Koranic decree of God, “Be and it was,” has smacked us into motion like a stick and ball and we are now rolling through both space and meta-space (makan o la makan).

This discussion echoes with the debate over free will and predestination. If Lucifer (Iblis) rebelled against God, did not God decree that rebellion? If Pharaoh oppressed Moses and the Jews, did not God harden his heart? Are not Satan and Pharaoh equally the servants of God, serving His purpose at His command, though they are condemned as evil? Rumi expounds this doctrine of evil’s hypostatized servitude to God with respect to Pharaoh (M1:2447ff.) and the proud archangel, Iblis.

Beyond the dualisms of obedience and rebellion, faith and unbelief, good and evil, all of which are produced by the multiplicities brought into being in creation, there is but one singleness, and in this Rumi sees the meaning of the Islamic doctrine of towhid — divine unity.

If you remain entranced by the outward forms, your worship is idolatry. One loves the essence of a thing and not just its outward forms, for the outward forms are secondary. Indeed, love gives rise to a multiplicity of forms, all contingent, just as God’s creation is contingent (Discourse 36, Fih 139). Likewise, the pilgrim at Mecca must not be concerned with the skin color of the man beside him; whether he be Arab, Turk or Indian, dark or light, his intention is the same color as your own.

Indeed, the fixation on a creedal form or a particular religious form becomes itself a failure to perceive the inner meaning, the central standpoint of oneness from which the multiplicity of signs radiates outward. When one looks at the glass of the lamp rather than the light radiating from it, it gives rise to duality and love of the lamp, whereas if one fixes one’s gaze on the light, it can be seen emanating from different lamps in various shapes and sizes: Mind of the universe! Point of view makes all the difference we see between the believer, the Zoroast, the Jew

Were it not so difficult to look beyond ourselves and focus on the end, the religions would never have come into conflict. One must try to learn to live with this dilemma and know when to look to the light and when to the lamp. To say “I am the Truth” as Hallaj did is a mercy, an intuition of the truth of unity, albeit one that you have to sacrifice your Self in order to see; whereas to say “I am lord,” as Pharaoh did, insistently foregrounds the lamp over the light and makes us accursed.

Many the believers, but their faith is One

One in soul, though many are their bodies.

References

Lewis, Franklin D. Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi. Oxford: One World Publications (UK), 2000.